Originally published by Quartz on June 12, 2019. Written by Adam Rasmi.

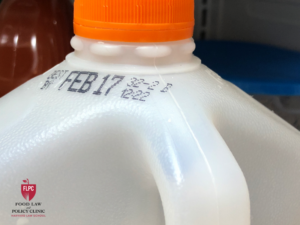

If you’ve ever found yourself in your local grocery store wondering what the difference is between “sell by,” “best by,” “expires by,” or “use by” food labels, you’re not alone. That confusion contributes to American consumers trashing $161 billion in food each year. Yet most people might be surprised to know that these labels often have very little to do with food safety.

Both the food industry and the US Food and Drug Administration are trying to change that, by encouraging companies to just use “Best If Used By” labels on groceries if the purpose of that label is “to indicate the date when a product will be at its best flavor and quality.” The FDA believes this standardized wording will help convey that foods “do not have to be discarded after the date if they are stored properly,” the FDA recently wrote in a recent open letter (pdf) supporting this change.

“We expect that over time, the number of various date labels will be reduced as industry aligns on this ‘Best if Used By’ terminology,” Frank Yiannas, the FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Food Policy and Response, said in a statement. The FDA doesn’t want consumers to rely on date labels alone to judge when to throw away food. Instead, the agency advises people examine food after its “Best If Used By” date for a noticeable change in “color, consistency, or texture,” and make the call about its quality. Consumers can also consult the agency’s FoodKeeper App, and its refrigerator and freezer storage chart.

That’s partly because most major food illnesses are a result of contamination issues, not freshness ones. “Weirdly enough, the taste or smell of a food doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s contaminated with a bug that’s going to make you sick,” Dr. Natalie Azar, a medical contributor at NBC, told TODAY. The FDA also acknowledges that manufacturers apply labels to foods for a variety of reasons, and usually not for safety.

Food date labels emerged decades ago in the US as a way for manufacturers to advise retailers on how long they could ideally stock an item. Americans flocking from rural areas with local stores, to cities with supermarkets stocked with pre-packaged foods, began to take more interest in freshness. As labels proliferated, confusion ensued: so much so that in 1977, New York state published a booklet guiding shoppers on how to decipher the codes. Most states now require date labels to indicate quality, while many even ban the sale of food after the labeled date.

Apart from infant formula, which is required by law to have a “use by” date, there has never been federal oversight over date labels. According to Emily Broad Leib, the director of the Food Law and Policy Clinic at Harvard Law School, one way large companies set dates is by hiring taste testers to sample a given product over different periods, and then report when they think something tastes stale or slightly off. And, “in states that require date labels on a lot of different foods, some small food companies that we talked to said, ‘We don’t have any money to do taste testing. We just pick a date out of thin air,’” Leib says.

These estimates are typically conservative, so the quality of food may still be fine long past the various best-by dates, Leib explains. While Leib welcomes the FDA’s push for standardization, she would ideally like to see federal guidelines for labels indicating quality and safety. “Federal legislation should require that manufacturers and retailers that choose to use date labels use only one of two standard labeling phrases: ‘BEST If Used By’ to indicate quality or ‘USE By’ to indicate safety,” she recently wrote.

In the past, she’s even recommended removing the labels from some foods—items like bottles of water, vinegar, or canned goods don’t expire for years. In the case of items where “nothing changes over time,” she says, “you don’t need a date on them.”

Health Law & Policy, Commentary

Medicaid Section 1115 Waivers for Reentry: Updates and Resources – Health Care in Motion

April 17, 2024